A year ago at this time, on the heels of one of the sharpest rebounds for domestic stocks in history, many folks wondered whether the advance was “real” or not.

A host of worries dominated headlines including a resurgence of coronavirus cases and social unrest. In fact, the first vaccine’s FDA authorization was still months away, and so too, were the November elections.

But we asserted then that markets are forward-looking (i.e., reflecting where the economy is headed, not where it is currently);that our economy’s resilience is consistently under (and mis)-estimated; that growing recognition of tremendous leaps in long-term human economic progress was squaring off against short-term Fears, Uncertainties, and Doubts (FUDs).

Fast-forward a year, return the value of the economy to pre-pandemic levels, slap another record advance on the market (S&P 500), and things are no different: the square-off between progress and disquiet continues.

But things are so different – this year versus last year – aren’t they? This year, we have vaccines developed faster than any other in human history that nearly half the country has already been administered. Social unrest seems to have abated.

Even in the face of clear and obvious progress we’ve made toward restoring domestic economic activity to some kind of normalcy, the FUDs of last year have given way to new FUDs of this year. Chief among them are the return of potentially pernicious inflation and profligate deficit spending that many insist will squelch continuing economic progress.

We have a different perspective. First, let’s set the table.

The Rip

Economics is frequently referred to as a “dismal science,” owing to a misguided perception that misery is an inescapable element of the human condition.1 Recently, Neil Irwin, who covers the dismal science beat for the New York Times offered 17 reasons “To Let the Economic Optimism Begin.”2 Two of those reasons included the idea that fiscal (The President & Congress) and monetary policy (The Federal Reserve, a/k/a “The Fed”) want to “let it rip”.

That got us to thinking: While what’s going on with fiscal and monetary policy could be thought of as a not-so-grand experiment, we know that the real “rip” originates from the “boots-on-the-ground” grand experimentation of normal, everyday “folks in their basement”. Cross-pollination of those experiments with other ideas among more minds happening faster than ever before in human history; that’s the rip that grows business’ sales, improves margins, and drives corporate earnings. Those corporate earnings pull stock prices upward, and that value/wealth creation process provides the foundation of resiliency propelling economies forward. More on this rip later.

The Fog

A retired former chief economist for a large money management firm whose market observations and commentary we follow with great interest recently wrote:

“Uncertainty is the enemy of investment, and investment is the source of growth and prosperity. An uncertain future inhibits growth by encouraging investors to choose safety over risky ventures which promise to enhance productivity and living standards. As my mentor John Rutledge used to say, inflation is like a thick fog that settles on the highway, forcing everyone to slow down. Deflation is just as bad. A strong and stable dollar is nirvana. Huge increases in the money supply coupled with massive deficit-fueled government spending is most definitely not nirvana.”3

So, there it is, context for our discussion that follows. As an array of factors are in place to expand and perhaps redefine parameters of economic recovery and growth, we believe the country is ready to “let it rip through the fog”.

Fiscal & Monetary Policy – An Experimental Rip With Uncertain Outcomes

Current thinking behind fiscal and monetary policies positioned to “let it rip” harkens back to supposed lessons learned during recovery from the Financial Panic of 2008. Back then, the argument for massive fiscal and monetary stimulus was at odds with the argument for discipline and prevention of “moral hazard”. Many at The Fed worried too much stimulus could lead to higher interest rates and runaway inflation.

The consensus on most sides of policymaking: to maximize economic growth potential and achieve full employment with only modest inflation, but without allowing higher interest rates to crowd out private investment, deficits should be kept in check. The Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 shifted consensus thinking on many sides.

Passed at the end of 2017, the Act was roundly criticized as fiscally irresponsible. Claims that it would pay for itself within a decade through stronger and faster growth were met with skepticism and derision.

By the end of 2019, however, even after a near 50% increase in the deficit, the country boasted the lowest unemployment rates since the 1960s, the inflation rate fell, and interest rates remained low and stable. In short, the economy was ripping. And so, influential thinking concludes, if previous economic orthodoxy was tethered to erroneous assumptions, maybe the time is right to experiment with those fundamental assumptions.4,5

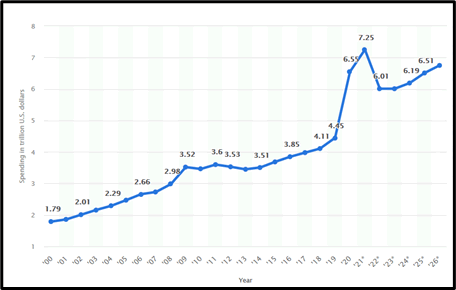

Chart 1 illustrates spending patterns by the federal government over the last 20 years and what they’re projected to be over the next five years. To be clear, these are outlays for spending only, not the deficit itself (that’s actually expected to contract in the out years). This is the fiscal policy experimental rip.

Chart 1: Total Outlays of The U.S. Government

(“Fiscal Policy Experimental Rip”)

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/200397/outlays-of-the-us-government-since-fiscal-year-2000/

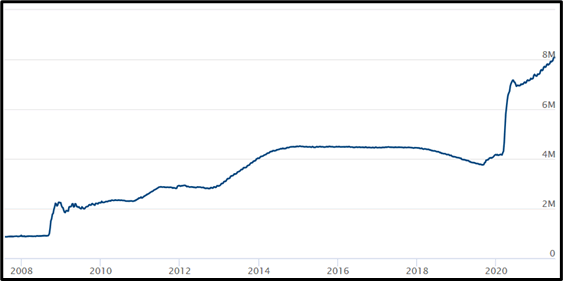

Chart 2 illustrates recent trends in the size of The Fed’s balance sheet. As part of their mission to promote and support liquidity in the financial system, The Fed buys and sells securities on the open market, the cumulative effect of which helps keep interest rates low. This is the monetary policy experimental rip.

Chart 2: Total Assets of The Federal Reserve

(“Monetary Policy Experimental Rip”)

Source: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm

A reasonable question might be: “If these fiscal and monetary experiments fail, don’t we run the risk of a crash?” To address this question, we turn to first principles.

First Principles

In April, in what would be a first for any space program in history, a private company called Space X sent astronauts to the International Space Station. But the accomplishment is noteworthy for many other reasons, including the ability to source and build reusable fuel rockets cheaper and more efficiently than even NASA could itself. How?

Nearly a decade ago, at a time when the stock market seemed inexplicably terrified with something called a “fiscal cliff”, serial entrepreneur Elon Musk, CEO of Space X (and, as it happens, Tesla Corp.), described how he thinks about solving problems:

“I tend to approach things from a physics framework. And physics teaches you to reason from first principles rather than by analogy. So I said, OK, let’s look at the first principles. What is a rocket made of? Aerospace-grade aluminum alloys, plus some titanium, copper, and carbon fiber. And then I asked, what is the value of those materials on the commodity market? It turned out that the materials cost of a rocket was around 2 percent of the typical price—which is a crazy ratio for a large mechanical product.”6

First principles thinking reduces a process to its most basic elements and builds reasoning from there. In theory, one “clears the decks” of all assumptions, and doubts every fundamental, until one is left with only indelible truth. James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, argues that in practice, however, you don’t have to dig to the core to accrue the benefits of first principles thinking, just a level or two deeper than other folks.7

Let’s try to apply a first principles framework to our understanding of what we know about U.S. stock results (i.e., its history).

First Principles & The Stock Market

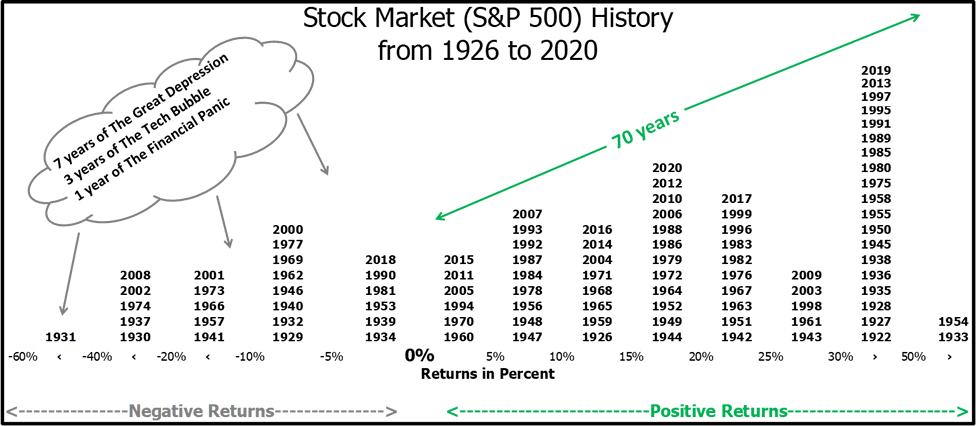

Chart3: U.S. Stock Market History

Source: Ibbotson Associates, Merrill Lynch

Chart 3 depicts a histogram of stock market results (S&P 500) from 1926-2020, a 95-year history of returns. What kind of reasoning can we build for this history applying first principles thinking?

- Of the 95 years, 70 years yielded results greater than zero percent. In other words, three out of four years yielded positive results.

- Of the 25 negative result years, almost half of them involve some speculative excess that needed to be purged or “corrected” (i.e., Great Depression, Tech Bubble, Financial Panic). In other words, despite all the focus on corrections and bear markets, garden variety negative years aren’t all that common. “Crashes” are rare!

The current growing acknowledgement that returns of late have been particularly strong is accompanied by growing anticipation of the next correction or bear market.

But the history behind the results in the histogram includes navigation through some of the thickest fog this country has ever faced including two World Wars (and several smaller ones), presidential assassinations and impeachments, terrorist attacks, and at least two global pandemics.

The Fog also includes previous periods of high corporate and personal taxation, double-digit unemployment, high inflation, budget surpluses, and not-so-grand experiments with massive deficits.

As we said in our introduction, our economy’s resiliency is consistently under (and mis)-estimated. The American stock market is a forward-looking reflection of that resiliency, and the histogram a reminder that from a first principles perspective, despite The Fog, the market advances far more often than not.

The Cause

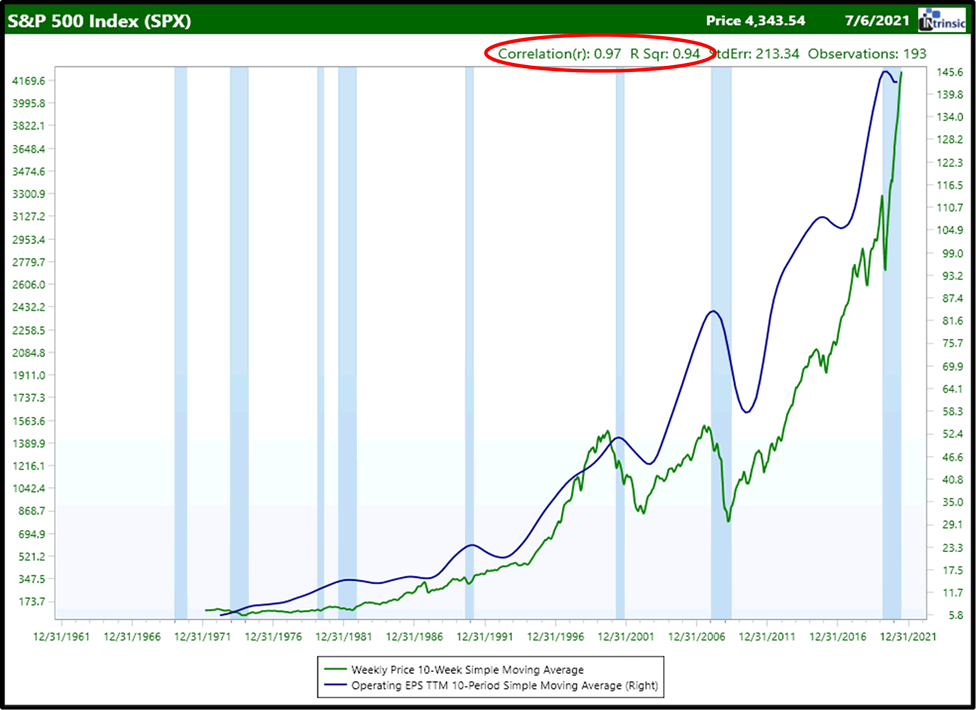

What causes stock prices to go up? First principles tells us, it’s earnings growth. Throughout history no single variable has been able to show a greater correlation to stock price growth than earnings per share growth. A statistical rule of thumb suggests correlations above .75 are considered to be “strong”.

Chart 4 shows a 50-year history between stock market prices and its earnings growth. The correlation of .97 is circled in red, and the R-sqr (short for R2) of .94 shows the degree to which movement of one variable (in this case stock prices) is explained by movement in the other variable (earnings per share). An R2 of “1” indicates a perfect positive correlation.

Chart 4: Earnings Growth and Stock Prices (1971-2021)

Source: Intrinsic Research

From a first principles perspective, the causal link between earnings growth and stock price appreciation is undeniable.

The Outlook for Earnings Growth

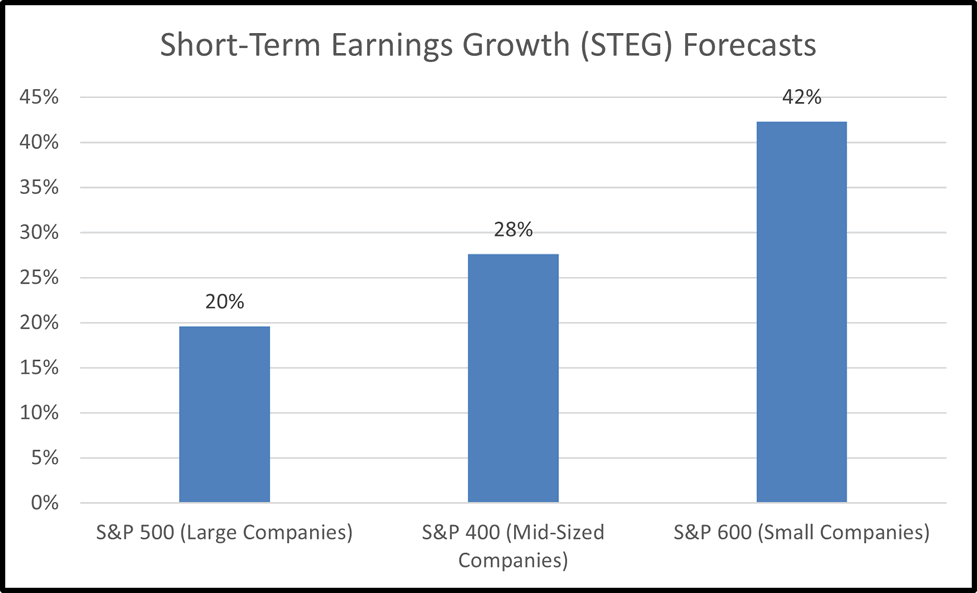

Building on the former observation, one next logical question might be: what’s the current outlook for corporate earnings growth? We adapted the next two charts from another former chief economist whose observations we follow and pay close attention to.

Chart 5: Earnings Growth Outlook Over the Next 12 Months

Source: Adapted from Yardeni Research Inc.: Stock Market Briefing: S&P 500/400/600 Relative Fundamentals, Page 10, July 7th, 2021

Chart 6: Earnings Growth Outlook Over the Next 5 Years

Source: Adapted from Yardeni Research Inc.: Stock Market Briefing: S&P 500/400/600 Relative Fundamentals, Page 10, July 7th, 2021

The S&P 500, 400, & 600 represent 90% of the stock market capitalization in the U.S. As such, they represent businesses of all sizes and industries.

As it stands right now, the earnings growth forecasts for these S&P groups are quite robust. Because they include a meaningful upfront boost from economic reopening, they will likely moderate over time. But even if we apply a haircut to all these estimates, the outlook for corporate earnings growth, particularly for the large-company S&P 500, is solid over both the short and long term. As an important aside, if and when aggregate corporate earnings slow, we believe our portfolio company earnings will remain better and faster on a relative basis.

The key question: Is The Fog (inflation fears and deficit spending) thick enough to force projected earnings growth to slow down or stop somewhere down the road? Our answer: While we believe The Fog’s effects are transitory and will abate over time, we are only just beginning to restart the post-pandemic economic engine.

The Most Interesting Reason

We promised to return to Irwin’s list, and what we believe is the most interesting reason to be optimistic about our economy.

- Reason #1: The ketchup might be ready to flow.8

Frequent readers of these pages know that we are big believers in the inherent dynamism of our economy, even if the benefits stemming from the innovation that fuels it are difficult to observe at first. Sometimes, innovation that begins as evolutionary later proves revolutionary in other ways. Writes Irwin:

“An innovation, no matter how revolutionary, will often have little effect on the larger economy immediately after it is invented. It often takes many years before businesses figure out exactly what they have and how it can be used, and years more to work out kinks and bring costs down. In the beginning, it may even lower productivity! In the 1980s, companies that tried out new computing technology often needed to employ new armies of programmers as well as others to maintain old, redundant systems. But once such hurdles are cleared, the innovation can spread with dizzying speed. It’s like the old ditty: “Shake and shake the ketchup bottle. First none will come and then a lot’ll.”9

Habits’ author James Clear offers an interesting first principles perspective on the ketchup bottle metaphor:

“The human tendency for imitation is a common roadblock to first principles thinking. When most people envision the future, they project the current form forward rather than projecting the function forward and abandoning the form. For instance, when criticizing technological progress some people ask, “Where are the flying cars?” Here’s the thing: We have flying cars. They’re called airplanes. People who ask this question are so focused on form (a flying object that looks like a car) that they overlook the function (transportation by flight). This is what Elon Musk is referring to when he says that people often “live life by analogy.”10

It took several decades for the First Machine Age (i.e., the Industrial Revolution) characterized by the steam engine, the printing press, and electrification to filter down to the masses and change the fundamental ways in which people were living.

Today, in this Second Machine Age, the filter-down process, characterized by exponential improvements in information and data exchange – of the kind Musk used to create his rockets for Space X – are, in many cases, happening instantaneously. The transformative effects of this kind of surge in human economic progress are the new fundamental drivers of corporate earnings growth. And that is the most interesting rip to get excited about!

Appendix: A Word About Economic Mismeasurement – Inflation Edition

As we have often stated, we believe many aspects of our economy are mismeasured. For example, frequent readers may recall our explanation of Mark Skousen’s gross output’s (GO) potential as a better indicator of economic growth than gross domestic product (GDP).

As Northwestern professor Joel Mokyr notes, “Aggregate statistics like GDP per capita . . . were designed for a steel-and-wheat economy, not one in which information and data are the most dynamic sector.”11

Today’s headlines pronounce the return of inflation, the likes of which haven’t been seen since the 1970s. Many argue the massive deficit spending we’ve put in place promote its pernicious return.

But what if measures of inflation like the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the GDP deflator, or the Fed’s preferred inflation barometer, the personal consumption expenditures price index (PCE) – measurements that are generally reported within a few tenths of a percent of each other – are all wrong to begin with?

Andy Kessler, a former Wall Street analyst who now writes op-eds for The Wall Street Journal characterized the measurement with the following:

“By the time the [Bureau of Labor Statistics] puts something new in the CPI basket, it’s already cheap, so it misses the massive human-replacement price decline. The CPI is good at freezing a lifestyle and standard of living and showing how it gets more expensive over time. Great. But the CPI absolutely doesn’t take today’s technology-infused lifestyle and work backward to show how much more expensive it would have been in [the 1970s].”12

During an interview with 60 Minutes, former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan explained:

“When new products go on the market, they come in at relatively high prices. Henry Ford’s Model T came in at a very high price, and the price went down as technology improved. You didn’t start to pick up the price level until well into that declining phase. So there is a bias in the statistic. You’re getting statistics which are not correct. If you had a 2% inflation rate as currently measured, it’s the equivalent of zero for actually what consumers are buying.”13

So, if actual inflation is being mismeasured (overestimated), it challenges the narrative that our current bout of inflation is a structural problem rather than a temporary one.

Sources & Notes

1 https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/12/why-economics-is-really-called-the-dismal-science/282454/

2 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/13/upshot/economy-optimism-boom.html

3 http://scottgrannis.blogspot.com/2021/05/the-fed-and-our-politicians-are-playing.html

4 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/11/upshot/trump-economy-lessons-biden.html

5 https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/05/28/biden-budget-deficits/

6 https://www.wired.com/2012/10/ff-elon-musk-qa/

7 https://jamesclear.com/first-principles

8 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/13/upshot/economy-optimism-boom.html

9 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/13/upshot/economy-optimism-boom.html

10 https://jamesclear.com/first-principles

11 Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, (Penguin Books, 2019), page 332.

12 https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-canard-about-falling-incomes-1528054223?mod=article_inline

13 https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-federal-reserve-is-flying-blind-on-inflation-11557688767